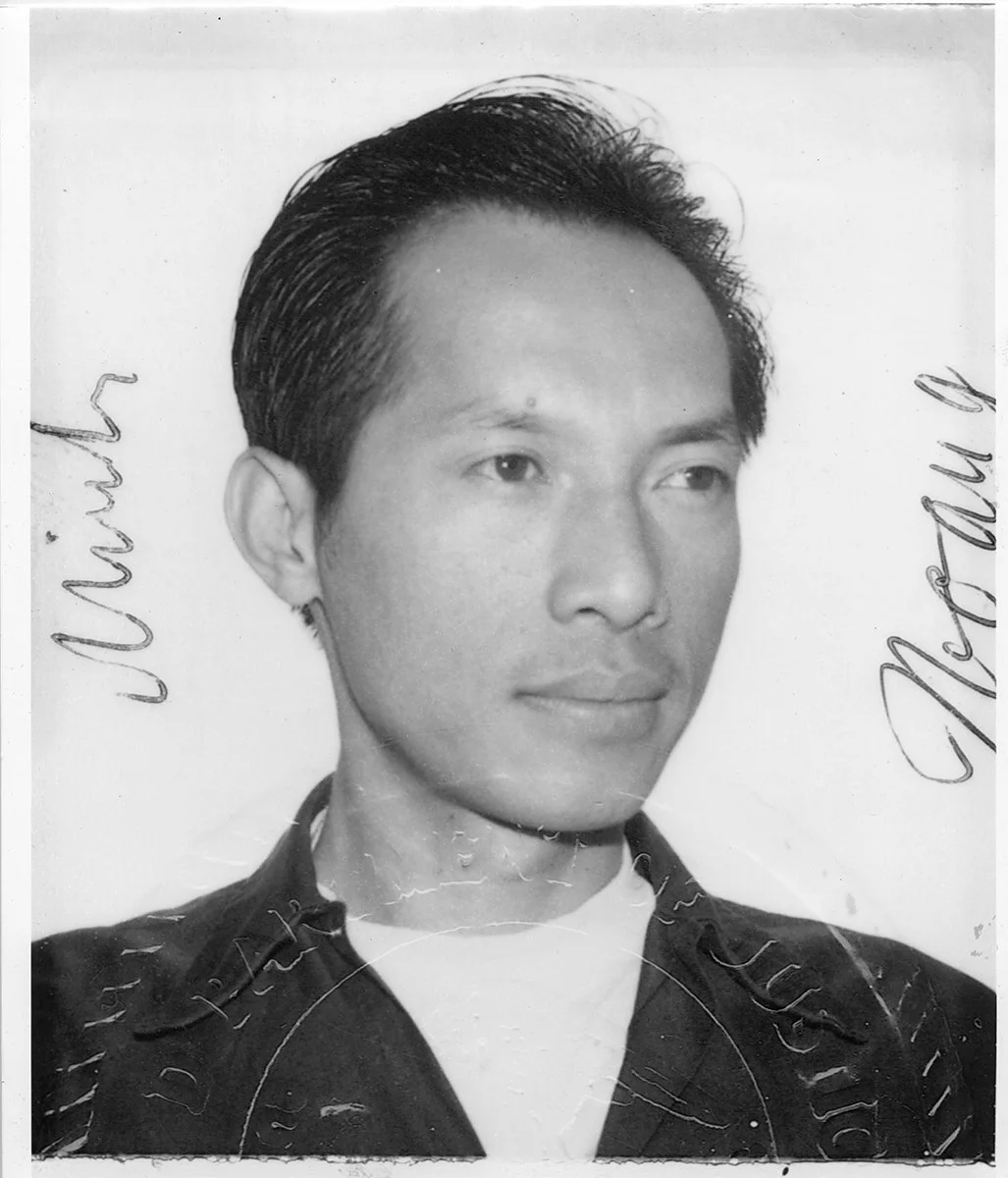

Growing up, I only had two photos of my father. One was a framed portrait of him that moved with my family from house to house alongside the altar that’s been in the corner of a living room for as long as I can remember. The other is his driver license with a photo. The two photos served as the only evidence that he existed here and in my life briefly. I could only imagine who he truly was based on the accounts of my mother and older siblings. And the two dimensional image of him frozen in that soft but direct gaze was housed on the midlevel of the altar until I began my early teenage years. My grandfather was dying of cancer and soon in the following weeks, my mom had taken a trip to Canada to be with her family. After the passing of my grandfather, she came to me with my father’s portrait in hand, telling me in a serious tone that it was time for me to look after my father’s portrait. But really, the portraits on the altars were not just portraits, but signifiers for the spiritual beings and ancestors that we as people have a responsibility to tend to. She didn’t have the capacity nor space on the altar to pray for and serve both my father and her father. It was time for me to take the responsibility.

It was my mom who’d deep clean the house every year on Tet, buy fresh fruits and flowers from the market and lay out the servings of rice, water and vegetarian food. She led every prayer and raked in all the blessings for our family. The altar was a part of her lifelong work and commitment to family.

My mom left Vietnam in the 1980’s to come to America and she made home in Oakland. She had friends from back home and her own Vietnamese community within Oakland. She has coworkers as well. She’d tell us about the customers at work that she’d meet and the conversations they had. There was also my childhood stepdad, and there was his mother and friends who lived down in San Jose. I remember visiting them often as a child and staying for weekends. I’d call my stepfather’s mom “Ba” and all the men in the house “Chu”, like an uncle. But me and my siblings, we were making our own diverse groups of friends and growing up in the Bay Area. Oakland really shaped our family’s life, except for my younger brother.

My mom had had my two oldest sisters Hien and Vickie at the young age of 19 and 20. Hien was the first born child and Vickie was born just a year later. Hien is the only sibling of mine with a true Vietnamese name on paper but the diacritics and tonality is lost in English. Vickie’s Vietnamese name is Tram, but I’ve only ever heard her called that in the home by our mom. Mom would call them “be Hien” and “be Tram” since they are her daughters, “be” meaning a girl child or baby girl. My third older sister, Ophelia, was called “Be Be”, like “baby” in English. I was simply called Boy and my younger brother “Hieu”. Maybe we’d become known by our outside English names so we’d fit in easier, or maybe it was because my mom realized we were being raised in a whole new environment. Looking at the old photos of my older sisters in their traditional Vietnamese clothing makes me realize that there was an attempt by our mom to pass down and carry on the traditions that she was raised on. She’d take us to celebrate and eat at the Great Mall in San Jose every Tet. She would invite us to set the altar every now and then. Over time though, we became just as American as we were Vietnamese.

I remember once meeting a Vietnamese friend in elementary school: Ronald Dinh. We’d been waiting to be picked up like the other kids, standing in front of Laurel Elementary after school. He’d asked me if I knew what part of Vietnam my parents were from, and explained to me that there are differences in dialect between the northern and southern regions. I hadn’t experienced that kind of curiosity about Vietnamese identity outside of the home at that age. Ronald was an outlier though because like my older sisters, I’d begin to make a diverse group of friends all around.

In the past, there was tension which strained relationships between us as a family but overtime, we’ve become stronger and more forgiving of each other, with more understanding of the context that we are growing through together. Our mom worked and took care of us as kids since the end of her teenage years. She told us to go to school and get good jobs, leaving us to the school system. Leaving us to locked doors at home after school and each other to take care until she returned from work at night. There was a collective desire as siblings for more attention, for a bigger community of support, for extended family, for a father figure. But all we had is our immediate family, separated by geography and grief from the rest of the connecting pieces. The stories I’ve received don’t span across the ocean to Vietnam from grandparents or even before the 90’s. The stories I’ve been told are mainly from my older sisters and their memories of young life as daughters of immigrants moving around Oakland, west to north to east. And the stories they received came from our mom. The maternal presence in the lives of me and my siblings can’t be understated. It’s only been more recently, since a trip to Vietnam, that I’ve been able to accept and understand how different my siblings and I grew up, compared to our mom with her siblings and mother. Seeing where my mom and my Ba Ngoai (mother’s mother) grew up in Ho Chi Minh/ Saigon put the experiences we each went through in a broader context of the world. Before, I didn’t understand the purpose of prayer, who to pray to or what we were praying for. I’d see our mom stand before Me Quan, the portraits and the Buddhas on the altar with eyes closed, incense lit. Picturing my father, I imagine he’s praying for a similar thing, before the cross in a Catholic church. Despite the different beliefs, I like to think that they both prayed for more compassion from the higher spirits and more compassion from us as their children with our needs since there was only so much that they could do. The stories passed down from grandmother to mother, mother to daughter and from sibling to sibling has helped us find more compassion for the struggles endured together.

Gospel

I'd been told that my name, Matthew, was inspired by my father’s Catholic influence and it took me until recently to understand how my name relates to the Bible. Childhood memories of being in Vietnamese classes on Sunday with Catholic church afterward are my earliest encounters with Catholicism. I fell asleep in church and soon stopped attending the extra schooling on weekends. I appreciate my mom’s efforts to raise me closer to my roots and despite my inactivity with religion, I’ve found deeper meaning in my name by coincidence. The words of Thich Nhat Hanh in an interview with Oprah come to mind when he references The Gospel of Matthew while talking about the power of living in the present moment. The verse mentioned (6:34) is the little bit of the Bible that I know thus far but in it, I’ve found a piece of truth.

—

I reflect often on what life would’ve been like with a father in my life. Maybe I would have continued on with Vietnamese school and Catholic church as a child and followed in his footsteps. I see his portrait on my bookshelf at home and wonder if my bigger blessings in life have yet to come because I haven’t picked up his beliefs, nor the rituals of my mom. The difference his presence could’ve made in my life makes me more appreciative for the women in my life: my mother and older sisters. And appreciative of these identities that we’ve formed as a family, growing together in the Bay Area. I wished at some point that my siblings and I were more traditional, more Vietnamese. But the openness to explore our own worlds and spiritualities was truly a blessing. Our mom allowed us to pick the cultures we’d gravitate towards while still showing us our roots through her action, practices and prayer. We couldn’t be anymore Vietnamese with our American first names, but we became our own unique thing: Vietnamese-American.

The portrait of my father was once housed in the midlevel of the altar that moved with my family from house to house until my grandfather’s eventually replaced his. I’d gaze into the portrait a lot when I was young, with questions of what my father was like and I’d been told things about him by my sister and mom. Through stories of his life as a father and stepfather to my older half siblings, he was described as many things: intelligent, calm, handsome, romantic, catholic, etc. But after one month old, he’s always been an idea in my life, and the ideal man to strive towards being in a way. Yet his portrait has always been in the background of my life, once on the altar upkept by my mom and now awkwardly crammed on my bookcase (sorry Dad). It’s one of only two photos that I have of him and they remind me that he once existed in my life briefly and now in spirit. I try to send him more messages by incense now and his portrait is always in the background, seeing when I leave and come home.

In contrast to having one conclusive portrait of my father for a whole lifetime, I use analog photography to preserve the passing present, create memories for the future and find beauty in the worthy moments. Recently, on my first trip to Vietnam, I tried to uncover more stories about my family history through elders but faced challenges such as trauma that’s hard to talk about, and I continue facing challenges such as geographical distance from family and a language barrier. And when I came home, I read Vietnamese authors and practiced the language to reconnect with what felt like a lost part of my identity. Reading other stories helped fill in the cultural questions of my story, and differed from the lived experiences of my sisters growing up in Oakland. But I didn’t need to read and practice what didn’t call to me in my youth to appreciate that the past of my family has gotten me to the present, and I don’t need to go poking at wounds to be in familial presence through conversation and in eating together. As much as I miss the stories and photos I never had, or think about the life that could’ve been in the land of my ancestors, I am Vietnamese-American. I won’t carry on every tradition that came before me but I can cheat the impermanence of the present moment by photographing it and making it last longer for when I need to spiritually and culturally reflect on where my story began. For when I need a reminder to come back to the present.

Matthew Hoang

Bio

My name is Matthew Hoang and I am a bay area born and raised photographer. As someone who's mind state is constantly in other places, physically here or not, photography is the perfect artistic medium for me because it keeps me focused on the people and places around me.